Friday, December 22, 2023

(click here to listen to or read today’s scriptures)

Incarnation for all of us

My soul proclaims the greatness of the Lord; my spirit rejoices in God my savior.

Christmas has been rearing up like an impatient reindeer, ready to streak across the skies following that amazing angel Gabriel, singing Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace.

I watched Miracle on 34th Street Wednesday night after spending a few hours with two boyish miracles Miles and Jasper, eating cookies in the apartment office, getting in line at the recycling dumpster, reading books for the last time before the books head for ADRN (the thrift shop where Aki and I volunteer once a week), and savoring root beer floats (after a healthy snack) in the middle of the afternoon.

The miracles abound. And in The Universal Christ, Richard Rohr tries to make sense of them, how to believe in them for all they’re worth. First Fr. Rohr describes three, to his mind, inadequate worldviews:

Those who hold a material worldview believe that the outer, visible universe is the ultimate and “real” world. People of this worldview have given us science, engineering, medicine, and much of what we now call “civilization.” A material worldview tends to create highly consumer-oriented and competitive cultures, which are often preoccupied with scarcity, since material goods are always limited.

A spiritual worldview characterizes many forms of religion and some idealistic philosophies that recognize the primacy and finality of spirit, consciousness, the invisible world behind all manifestations. This worldview is partially good too, because it maintains the reality of the spiritual world, which many materialists deny. But the spiritual worldview, taken to extremes, has little concern for the earth, the neighbor, or justice, because it considers this world largely as an illusion.

Those holding what I call a priestly worldview are generally sophisticated, trained, and experienced people that feel their job is to help us put matter and Spirit together. The downside is that this view assumes that the two worlds are actually separate and need someone to bind them together again.

So.

I read this in the middle of the night when I woke up to go to the bathroom. Maybe that’s the best time for me to read theological philosophy, or philosophical theology, or … Rohr continues with thoughts about a fourth worldview, the one that he prefers:

In contrast to these three is an incarnational worldview, in which matter and Spirit are understood to have never been separate. Matter and Spirit reveal and manifest each other. This view relies more on awakening than joining, more on seeing than obeying, more on growth in consciousness and love than on clergy, experts, morality, scriptures, or prescribed rituals.

In Christian history, we see an incarnational worldview most strongly in the early Eastern Fathers, Celtic spirituality, many mystics who combined prayer with intense social involvement, Franciscanism in general (Rohr is a Franciscan), many nature mystics, and contemporary eco-spirituality. Overall, a materialistic worldview is held in the technocratic world and areas its adherents colonize; a spiritual worldview is held by the whole spectrum of heady and esoteric people; and a priestly worldview is found in almost all of organized religion.

The moon will be full in four nights. The star that led the wise men to Bethlehem might be full in just two, on Christmas Eve, when the hopes and fears of all the years “are met in thee tonight.” Can we believe it, can we just be still, be silent, and believe it? Rohr thinks we can, and furthermore that this is the only way for us to live, so that all of life is prayer:

An incarnational worldview grounds Christian holiness in objective and ontological reality instead of just moral behavior. This is its big benefit. Yet, this is the important leap that so many people have not yet made. Those who have can feel as holy in a hospital bed or a tavern as in a chapel. They can see Christ in the disfigured and broken as much as in the so-called perfect or attractive.

Mary’s song catches our attention in just this broken world:

He has cast down the mighty from their thrones and has lifted up the lowly. He has filled the hungry with good things, and the rich he has sent away empty.

Mary sings of the now and not yet, as do all the poets and prophets of the Scriptures. God’s hesed is never in doubt, more visible and even attainable in suffering than in comfort. God never stops loving me, and so I need never stop feeling loved and loving myself, passing it all along to everyone around me, no matter what. Rohr concludes:

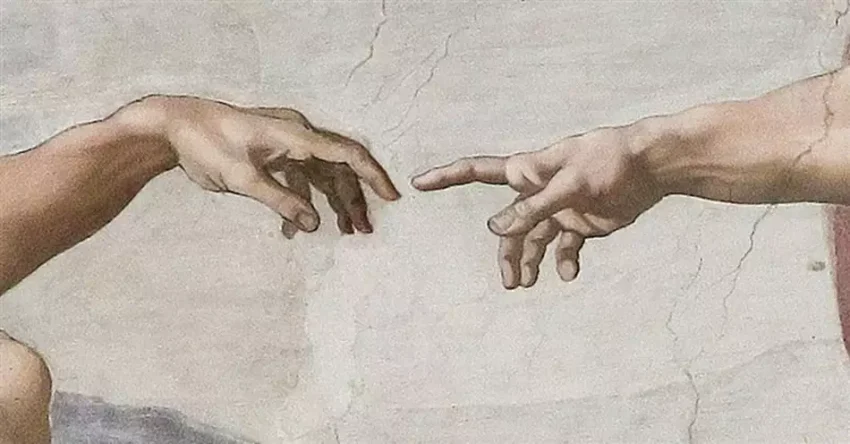

They can love and forgive themselves and all imperfect things, because all carry the Imago Dei equally, even if not perfectly. Incarnational Christ consciousness will normally move toward direct social, practical, and immediate implications. It is never an abstraction or a theory. It is not a mere pleasing ideology. If it is truly incarnational Christianity, then it is always “hands-on” religion and not solely esotericism, belief systems, or priestly mediation.

And Mary too concludes her song, in reverence and confidence:

He has come to the help of his servant, for he remembered his promise of mercy, the promise he made to our fathers, to Abraham and his children forever.

(1 Samuel 1, 1 Samuel 2, Luke 1)

(posted at www.davesandel.net)

#